- Born 1801 Virginia

- Free Black Craftsman

- Maker of Fine Furniture

- Successful Businessman

- Lived Milton 1823-1861

- Died c. 1861

Click Photograph for Larger Image

|

|

Thomas Day, probably the most famous craftsman to call Caswell County home, was born 1801 to free black parents in Dinwiddie County, southeast Virginia. His father was John Day, a farmer and skilled cabinetmaker whose products apparently were well-received in the local market. According to the letters of John Day, Jr., only discovered in 1995, John Day, Sr., was the illegitimate son of a white South Carolina plantation mistress and her black coachman. John, Jr., names R. Day of South Carolina as his grandfather. Thomas Day's mother was Mourning Stewart, the daughter of free mulatto Thomas Stewart, who owned a large and successful plantation in Dinwiddie County on which he worked slaves. John Day married Mourning Stewart around 1795-1796, and they had two sons: John Day, Jr., born 1797; and Thomas Day.

Both John, Jr., and Thomas were educated to an extent unusual for free blacks in the South. It is believed that both attended school with white students in Sussex County, Virginia. That both were very literate and well-educated is obvious from the correspondence they left behind.

By 1817-1820, the Day family had moved from Virginia to Warren County, North Carolina, east of Caswell County. It is possible that John Day, Sr., was employed in Warren County by Thomas Reynolds, a well-known local master cabinetmaker who operated a shop in Warrenton (and was know to have employed black labor). John Day, Jr., who had followed his father to North Carolina to continue learning the wood-working business, apparently set up his own shop.

It was John Day, Jr., that led the way to Milton, North Carolina. His education had introduced him to religious thought. In 1820, he was baptized into the Baptist faith. However, it was a Methodist minister by the name of Gardner who recognized the talents of John, Jr., and placed him in the pulpit to preach. In 1821, John Day, Jr., became licensed to preach. In 1822, he moved to Milton to study with Abner Wentworth Clopton at the Milton Female Academy. There he purchased property and established a cabinetmaking business to fund his religious studies. Thomas Day followed his brother to Milton, but exactly when is not known. However, it appears that Thomas had relocated to Milton by 1823. The brothers worked together in their furniture business and immediately were successful, even though they were not without white competition. By 1825, John Day, Jr., had departed Milton, returning to Virginia and leaving to his brother the cabinetmaking enterprise that was to make Thomas Day a legend.

While Thomas Day may have operated an independent cabinetmaking shop before joining his brother in Milton, it is there that his trade flourished and his reputation grew. In 1827, Day purchased property on Milton's main street and advertised his products in the Milton Gazette & Roanoke Advertiser newspaper:

That year he appeared for the first time on the tax list as a property owner. And, over the years he was to increase his property holdings.THOMAS DAY, CABINET MAKER, Returns his thanks for the patronage he has received, and wishes to inform his friends and the public that he has on hand, and intends keeping, a handsome supply of Mahogoney, Walnut and Stained FURNITURE, the most fashionable and common BED STEADS, & which he would be glad to sell very low. All orders in his line, in Repairing, Varnishing, & will be thankfully received and punctuallo attended to.Thomas Day married Aquilla Wilson in Halifax County, Virginia, on 6 January 1830. Aquilla Wilson was born c. 1806 in Halifax County. The couple had three (possibly four) children: Mary Ann, born c. 1831; Devereaux, born c. 1833; Thomas, Jr., born c. 1837; and, possibly a daughter, A., born c. 1835. This last child may have been named Aquilla after her mother. All children are believed born in Milton.

Many stories have circulated about the difficulty Thomas Day and Aquilla Wilson had in becoming married. One states that she was not allowed to travel from Virginia to North Carolina to marry Day. However, the facts show that Thomas Day married Aquilla Wilson in Halifax, Virginia, and that the difficulty arose when the couple attempted to return to Milton. The year was 1830. The problem was a North Carolina law passed in 1826 in an attempt to restrict the movement of free blacks into the state. It required nothing short of a special act adopted by the North Carolina Legislature to permit Day's new wife into North Carolina. The support he received in this effort was almost universal, including a letter from Romulus Mitchell Saunders, North Carolina Attorney General and former state legislator and U.S. Congressman (and born in Caswell County near Milton).

Day's economic and social position was unique. He was a free black, but owned slaves. His social position was below whites, but he had white apprentices. Only whites were allowed to sit on the main floor of the Milton Presbyterian Church, except for Thomas Day and his family. He and Aquilla were accepted as full members of the church in 1841. The pew in which he sat, he made. And, it was on the front row, not in the back. Local tradition has it that Thomas Day traded building pews for the church in return for his family's being able to sit in the main portion of the sanctuary. This is, however, doubtful as it was not his style. Thomas and Aquilla were accepted as full members of the church, and it is possible that he was an elder.

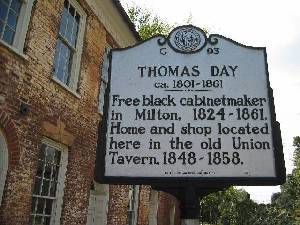

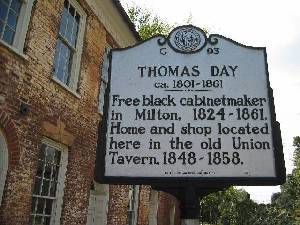

Day owned his place of business and residence, adding a brick addition to contain his workshop. This is the historic Union Tavern (Yellow Tavern) in Milton. He became a major stockholder in the local branch of the North Carolina Bank and owned property beyond Milton. Given the time in which Day lived, this was remarkable. However, he was a remarkable man. He carried a standard line of furniture in Milton, but built custom furniture for the wealthy. He did work for governors, universities, and not just furniture. He created mantles, stairs, window and door frames, newel posts, and other decorative and functional trim. His operation became one of the largest furniture/cabinetmaking businesses in North Carolina, at one time employing twelve laborers.

In the late 1850s, Day's business suffered financial setbacks. A national panic in 1857 caused widespread financial difficulties from which Day did not escape. Moreover, he was faced with increasing restrictions on what he was allowed to do as a free black. By the end of the decade, Day's business was in receivership, and the court named his friend and business partner Dabney Terry as trustee for the property, which included his house and shop, tools, steam engines, rental properties, wagons, furniture inventory, teams, harnesses, and six slaves. The court gave him until December 1859 to settle is accounts. Thomas Day, Jr., executed a note for his father's debts, and the property was returned to him, but still under the eye of a court-appointed trustee. Thomas, Jr., continued the business through the Civil War and well into Reconstruction, selling out in 1871 and leaving Milton.

In 1861, Thomas Day disappeared from the Milton public records, and it is possible that he died that year. This death year is supported by Milton locals. He is buried near Milton on private property that he once owned. For many years only a pile of stones marked his grave. However, a suitable monument now memorializes the site.Thomas Day left behind an incredible legacy in his furniture, cabinetry, and other woodwork. His pieces can be found at the University of North Carolina, and in museums and fine homes throughout North Carolina and beyond. His Union Tavern, now a National Historic Landmark and on the National Register of Historic Places, is being restored. Remarkable is that his products were in demand for almost forty years. His work regularly is shown in special exhibitions, featured in publications covering black artisans, and, of course, remains evident in many Caswell County homes. The North Carolina Museum of History in Raleigh has a special collection of his work.

Here are the thoughts of Rodney D. Barfield in Thomas Day: African American Furniture Maker, (2005) at 29 (upon which much of the foregoing is based):

What has kept the name "Thomas Day" alive in the annals of southern history through the hardening of racial attitudes of the 1840s and 1850s and even the Civil War and Reconstruction is his incomparable craftsmanship and the refusal of his adopted home to let his merits go unnoticed. His furniture and interiors stand as irrefutable evidence of his skills, tangible evidence of an expert artisan of character and grace. While the achievements of other free blacks of antebellum North Carolina have been buried under a landfill of history weighted with racial antagonisms, Thomas Day's accomplishments are too exceptional and too tangible to ignore.

While the focus of this article is Thomas Day, it would be an oversight not to tell more about his brother John Day, Jr. It appears that John, Jr.'s ambitions within the Baptist church ran into difficulties in Virginia. This caused him in 1830 to move to Liberia as a colonist. There he had a most-distinguished career. He was one of the founders of the colony, Chief Justice of the Supreme Court, teacher, missionary, and official within with Southern Baptist Convention. It is in the letters that he wrote to the Foreign Mission Board of the Southern Baptist Convention that he revealed what we know about his life and that of his brother. These letters only came to light in 1995.