|

Much of the foregoing is based upon An Inventory of Historic Architecture: Caswell County, North Carolina, Tony Wrenn and Ruth Little-Stokes (1979) at 3-8. The Caswell County Historical Association published this book in 1979, and it remains for sale. See: CCHA Store.Caswell County, located in the North Carolina Piedmont on the Virginia border, has one of the largest and most distinctive collections of antebellum architecture in the state. This has been recognized by the establishment of two National Historic Districts (Milton and Yanceyville). The county also has one National Historic Landmark (that also is a North Carolina State Historic Site) and numerous buildings on the National Register of Historic Places. Caswell's built environment is a product of its climate, its location in the geographic and cultural subregion known as the "upland South," and its dominant tobacco economy and the resulting orientation toward markets and mores of middle Virginia. These structures include houses, outbuildings, churches, stores, factories, and bridges built from settlement around 1750. Most of the historic properties date from the 19th century, when tobacco made Caswell one of the wealthiest counties in the state. In 1850, over half of Caswell's population was enslaved, and only five counties in North Carolina had a larger enslaved population on the eve of the Civil War. This combination of a wealthy planter class supported by enslaved labor and the proximity of sophisticated Piedmont Virginia architecture resulted in the construction of an extensive group of substantial, architecturally distinctive farmhouses. The prolonged economic decline of Caswell following the war prevented the replacement of these houses by more modern designs. This riches to rags story resulted in the preservation of a rich heritage.

Caswell's historic architecture reflects the development of tobacco cultivation in the county. During the late 18th and early 19th centuries when the burley leaf was cultivated, the gap between large two-story farmhouses and one and one-half story cottages is striking. Housing built for subsistence farmers and those constructed for tobacco planters differ considerably during this period. The Bright-Leaf era began with the discovery of the charcoal-curing process that produced Bright-Leaf in 1839 on the plantation of Abisha Slade in the Blanch community. The higher price of this new yellow leaf at market greatly increased the demand for Caswell County tobacco, and the resulting widespread affluence provided the means to construct grand homes. The dominant house type became a two-story farmhouse with moderate architectural pretension. This type, labelled the "Boom Era" house, is a boxy frame house with exterior Greek Revival style decoration concentrated on the entrance and porch. The Boom Era house is a rural form, closely linked to the tobacco plantations. Rural Boom Era church buildings must have been constructed of log or frame, and nearly all have been replaced by more modern structures.

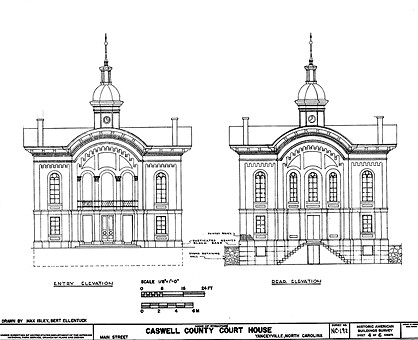

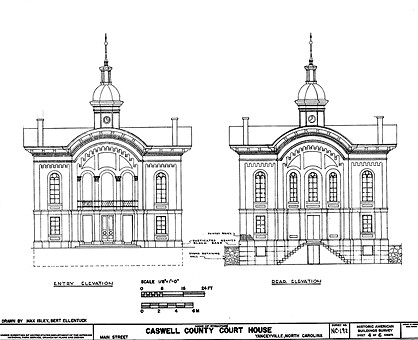

The only urban concentrations of buildings grew up around the three county "towns," Leasburg, Milton, and Yanceyville. Here other house types evolved. The earliest remaining church buildings in the county, of Greek Revival design in red brick, date from this period and are located in the towns. Caswell's few public buildings, the 1859 Milton State Bank and the magnificent 1861 courthouse, are embodiments of the prosperity and pride of this era. They represent the experiments of regional architects and builders with eclectic Victorian styles not present in conservative domestic architecture.

The dominant cultural influence on the county was Virginia. Even the smaller houses were apparently tinged by Virginia's tradition of architectural pretension, for Caswell's built environment is self-consciously stylish. With the exception of the smallest log houses, careful attention was paid to such details as roof lines, and molded cornices closed off at the corners with decorative pattern boards are standard features on both cottages and large houses. Plantation houses such as the Moore-Gwyn House and the Brown-Graves House in Locust Hill, set on high foundations, symmetrically landscaped with boxwood paths and set at the end of drives lined with cedars, are extensions of the Piedmont Virginia idiom. The rows of outbuildings -- slave cabins, smokehouses, dairies, and kitchens -- which define the "back yard" of several of the plantations, fit into the same tradition. Caswell's small frame and brick cottages and simple two-story houses with vernacular classical trim, as well as such elegant urban designs as the Thomas Day House/Union Tavern with metal sunbursts in the entrance fanlights, are typical of the architecture of Middle Virginia.

Seventy percent of Caswell's historic architecture is constructed of frame, 20% of log, and 10% of brick. The large log proportion is typical of Piedmont North Carolina; the high percentage of brick construction is atypical. Chimneys are built predominately of brick, although fieldstone is also used.

Over the decades, we have collected hundreds of photographs of Caswell County buildings (and other structures). Many of these have been placed online as part of the Caswell County Photograph Collection. There you will find the images catalogued by, among other categories, the nine Caswell County townships. However, Caswell County buildings of interest also will be found in other parts of the Collection, including:

While many Caswell County structures are older, none have the physical and overall historic presence of the magnificent Caswell County Courthouse. Many images are included in the collections referenced above. However, to go directly to these photographs see: Caswell County Courthouse. For more background on the building go to History of the Caswell County Courthouse.

The Caswell County Courthouse is indeed imposing. While the structure is on the National Register of Historic Places, it has not been designated a National Historic Landmark nor a North Carolina State Historic Site. Those honors are reserved for the Thomas Day House/Union Tavern in Milton, Caswell County. On May 15, 1975, it was designated a National Historic Landmark, and in February 2024 the Thomas Day workshop became a State Historic Site. Site themes are craftsmanship, social history, economic history, education and life of Free African Americans in North Carolina. National Historic Landmarks are historic properties that illustrate the heritage of the United States. They come in many forms: historic buildings, sites, structures, objects, and districts. Each landmark represents an outstanding aspect of American history and culture.