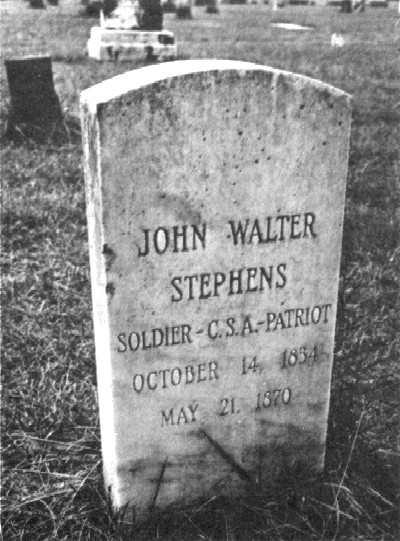

John Walter Stephens (14 October 1834-21 May 1870) was born near Bruce's Crossroads in Guilford County, North Carolina. He is the oldest child of Absalom and Letitia Stephens, who also had three other sons (James, William Henry, and Thomas M.) and a daughter (Letitia). When John was a young boy, his family moved to Rockingham County, North Carolina, first to Wentworth and then to Leaksville. His father, a taylor, died in Leaksville around 1848. The extent of his education is unknown. He married Nannie E. Walters (or Waters) in 1857. She died two years later, leaving Stephens with an infant daughter (Nannie). He remarried in 1860 (Martha Frances Groom of Wentworth), who also gave birth to a daughter (Ella).

Stephens was active in the Methodist church and became an agent for the American Bible and Tract Society for approximately a year. He subsequently entered the tobacco business, becoming a tobacco trader and moving to York, South Carolina.

At the start of the Civil War, Stephens apparently was in Greensboro and served as an agent commandeering horses for the Confederate army. At some point he moved to Wentworth. There is believed to have been an "impressment agent" for the Confederate Army, a position that required him to muster draftees. He was not in the armed service until near the end of the war, after which he returned to Wentworth and again worked as a tobacco trader. It was during this period that he allegedly had difficulties with a neighbor, Thomas Ratliff, over a trespassing chicken that Stephens mistook for his own. As the story goes (and there are several versions), Stephens killed the chicken, his neighbor compained to the sheriff, and Stephens spent a night in jail. Upon being released, Stephens purportedly confronted Ratliff with a seven-shot revolver and, as the fight progressed, two bystanders were wounded when the pistol accidentally discharged. This incident eventually led to the slurring political epithet applied to him by his enemies: "Chicken" Stephens. Unknown is whether Stephens faced further legal difficulties as a result of these actions.

Stephens moved to Yanceyville in 1866, continuing to trade tobacco and subsequently serving as an agent of the Freedmen's Bureau. He was an active member of the Union League and the Republican Party. His efforts to assist and organize politically the majority black population of Caswell County made many political enemies among the conservative white Democratic minority. Because of his popularity among blacks, Stephens was elected to the North Carolina Senate in 1868, displacing the long-standing Caswell County political veteran, Bedford Brown. This increased the hatred felt by many of the white citizens of Caswell County.

Stephens was socially isolated within the white community, expelled from the Methodist Church, and accused of many crimes, including the murder of his mother and burning crops, banrs, and other buildings, none of which resulted in any criminal legal action against him. As a result of threats made against his life, he was always well-armed, he fortified his house, and he carried a substantial life insurance policy (reported to have been $10,000).

This hatred of Stephens by the white Democrats, coupled with the much disliked Congressional reconstruction policies, resulted in Stephens purportedly being tried and found guilty by the Ku Klux Klan. The sentence of death allegedly was carried out by Ku Klux Klan members on May 21, 1870, in the Caswell County Courthouse in Yanceyville. He was stabbed, choked, and left dead or dying on a wood pile in a rear room on the ground floor of the Courthouse. The members of the murder party purportedly were: Ku Klux Klan leader John Green Lea(1843-1935); former Caswell County Sheriff Franklin A. Wiley (c.1825-1888); Captain James Thomas Mitchell (1828-1898); James G. Denny (born 1847); Joseph R. Fowler (born c.1844); James Thomas (Tom) Oliver (1843-1883); Pinkney Kerr (Pink) Morgan (1849-1930); and Dr. Stephen Tribue Richmond, M.D. (1824-1878).1

The Caswell County coroner's jury concluded that John W. Stephens "came to his death by strangulation caused by a small rope drawn around his neck in a noose and by three stabs with a pocket knife, the blade of which is about three and half inches long . . . done by the hands of some unknown person, or persons. . . ." Reports also circulated that one of his ankles was broken, presumed to have happened as Stephens fought for his life. Some have reported that he was a powerful man who would require great force to subdue. However, there are contrary reports indicating that he was a small thin man. No image of him has been found.

It was in response to this lawlessness and similar activity in Alamance County (murder of Wyatt Outlaw) that North Carolina Governor William W. Holden declared martial law, suspended the writ of habeas corpus, and sent Colonel George W. Kirk to Yanceyville to restore order. This episode in Caswell County history has become known as the Kirk-Holden War.

The facts with respect to this episode remain elusive. While the events took place over a century ago, local feelings remain surprisingly strong with respect to the "true story." Some historians believe that Stephens was a political and racial moderate who counselled his black constituents against physical retaliation following white terrorist attacks. Some are harshly critical of Stephens as an opportunist who used the newly freed blacks for his own gain and needlessly infuriated the local white populace.

Much of what we do know comes from one side of the story, the Ku Klux Klan side. The leader of the Ku Klux Klan group that murdered Senator John W. Stephens, John G. Lea, authored a confession and a detailed description of the events surrounding the murder. He did this in a written statement prepared in 1919 for the North Carolina Historical Commission, with the stipulation that it remain sealed until his death. This condition was honored, and the statement remained sealed until the death of Lea in 1935. See the Lea Confession for the full text of this document.

Stephens purportedly was well-armed, and at least one of his pistols (taken from him by his assailants) is on display at the Richmond-Miles History Museum in Yanceyville, North Carolina. See: Senator John Walter Stephens Pistol. The serial numbers associated with his pistols are: 5738 and 199934.

Go to the Kirk-Holden War section of this website for further information on the events that transpired after the murder of John W. Stephens, including the impeachment of Governor William W. Holden and his subsequent removal from office.

A documentary film The Murder of John Stephens was made by Piedmont Community College (Yanceyville, North Carolina).

Reference also must be made to Guilford County Superior Court Judge Albion Winegar Tourgee. He was a Northern Republican who had moved to Greensboro after the Civil War, became known for his attempts to bring the Ku Klux Klan to justice, and was a friend and advisor to Senator John Stephens. His book, A Fool's Errand: A Novel of the South During Reconstruction, published in 1879, is believed to be more fact than fiction. There he covers the John Stephens murder and views the events much differently than did John G. Lea. Also of interest is the letter that Tourgee wrote soon after the Stephens murder. See Tourgee Letter.

What happened to the family of John Sephens, his wife and two daughters, after the murder? Little is known. The 1870 United States census shows Martha Stephens, age 36, as the head of a Yanceyville household that included step-daughter Nannie (age 12) and blood daughter Ella (age 3). Also in the household were Letitia Stephens (age 22), believed to be the younger sister of Senator John W. Stephens, and William Stephens (age 30), a brother.

What remained of the Stephens family did move away from Yanceyville, and their house stood vacant for many years. Whites would not live there due to the remaining stigma attached to the property. Blacks, due to the social mores of the time, could not live there. Eventually, the house was purchased in 1906 by several prominent black residents and donated for use as a school for black children. This old house eventually became known as the Yanceyville School. The 1906 deed transfering the property shows the Stephens daughters living in Tennessee.